Healing the mind

Penny Griffiths-Morgan • 28 November 2020

Most people have heard of the term “shell shock”, although many researchers and observers of World War One history do actually state that it is not an accurate moniker for this particular condition.

An awareness of mental health and the vagaries of the psyche has become more prevalent in recent years with those suffering with conditions like depression, PTSD and others being treated with much more of a sympathetic hand, but why then does a stigma still attach itself to these conditions?

I wrote recently about Dirk Bogarde, and his experiences when he was one of the early visitors to a newly liberated Bergen Belsen concentration camp in 1945, the things that people experience during war are definitely horrendous but why was it only in the 20th century that it seemed to affect people on a psychological level quite so much?

If you look at battles pre 1914, they did not involve some of the killing machines that were to come, yes cannon balls would cause a lot of damage and ultimately death, but maybe it was not quite so overpowering? The difference in 1914 and onwards was the sheer madness and wanton destruction that would come from mechanised warfare, can you imagine being told to walk into a storm of machine gun fire? Can you picture not knowing if the projectile that had been launched from a mile away was going to obliterate where you were standing? Can you feel the terror that a soldier would have felt being buried alive in a crater and knowing that the chances of being rescued were virtually zero whilst the fighting continued?

Most of these were volunteers, they were not hardened military men, they were normal Joe’s who had either been conscripted or stepped forward to fight for their country, and for some, the mental injuries they were to suffer was possibly worse than death.

One of the most well-known Psychiatric pioneers of the Great War was the amazing WHR Rivers, who had his own military heritage in that his Uncle was on the HMS Victory and the same Uncle also purported to have been the one to shoot the enemy combatant who caused the fatal injury to Nelson.

WHR Rivers was a multi-talented man, not only was he a psychiatrist, he also worked as a neurologist, ethnologist and an anthropologist. It was after a research tour as the latter in Melanesia (Fiji, Solomon Islands etc) that he returned to Blighty in March 1915 and discovered a world at war. He immediately applied to the powers that be to offer his medical services and was posted to Maghull Military Hospital (also known as Moss Side) in Liverpool which was called “the centre of abnormal psychology”. Maghull was the first of its kind and by specialising in the area of shellshock, it managed to stop a large number of military personnel being sent to asylums where their treatment would not have been so targeted to their particular needs.

After a year, Rivers moved on the infamous Craiglockhart Hospital near Edinburgh, where not only was he able to achieve a childhood dream of being accepted into the military as a Captain with the Royal Army Medical Corps (something denied to him previously due to weaknesses from a protracted bout of typhoid as a teenager) but he also began a friendship that was to continue well after 1918 with poet Siegfried Sassoon.

His methods of treatment were not limited to the conventional ways of treating shellshock, psychoanalysis, dream interpretation and hypnosis being the norm, he also promoted talking cures, believing that by revisiting the events which triggered the persons mental break would be cathartic and help to heal them.

What I find most rewarding about Rivers’ attitude was that he did not see those who suffered with shell shock (or war neuroses as it was also known) as being cowards or malingerers, snipers who had suddenly lost their sight, men who had gone over the top and were now unable to walk, others who would lose all senses if they heard certain noises and trash everything in sight in an uncontrollable panic – these were not fakers, they were unwell.

Many of those suffering with shellshock were never able to return to duty, and this was something that Rivers’ struggled with during his time at Craiglockhart, he knew that by “healing” these men he could give them a modicum of a normal life, but he also was cognisant of the fact that they could also be sent back to the front and be met with their death…or a relapse.

The British Army is believed to have treated over eighty thousand cases of shell shock, but I would wager that the number was far higher and many would rather end their life than admit what they were conditioned to see as weakness.

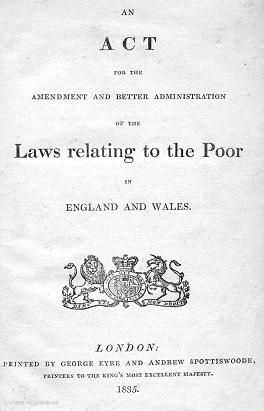

History has a tendency to repeat itself, antagonism towards certain groups of society can be seen through centuries of the past, and yes, it sadly is doomed to keep happening. Take the Jewish massacre in York in 1190 for example. Most people have either seen, visited or at least heard of Clifford’s Tower in the city. Originally constructed as a wooden keep by William the Conqueror (and therefore part of the castle), it was rebuilt in stone around 1245 or so but what happened to the original building? In the Middle Ages, it was against the Christian religion to lend money for interest, the religious teachings saw “usury” as being a sin, it was throwing the concept of charity and helping thy neighbour into the bin. The addition of interest payments on the loan was basically profiteering from another person’s misfortune and kicking them in the proverbial teeth whilst they were down. Not so in the Jewish faith, which meant that many became money lenders to Barons and other nobles who were desperate for funds to build their castles and such like. Those nobles included King Richard I who was in 1190, about to embark on another of his heavily leveraged crusades. As we have seen in more modern times, it is not difficult to incite unrest amongst crowds, especially when it is using a religion or way of life which they do not understand. Feeling this unease and being guaranteed royal protection, many of the Jews of York asked for help, and were granted cover in the timber tower that we know now as Clifford’s. Rumours had spread that the King had ordered a massacre of the Jewish population – not true, he actually defended them, as evidenced in London the year before– which would have been terrifying to those trying to live peacefully. Trust broke down between the Jewish community in the tower and the keeper, and when he left to run errands, they locked him out and refused his re-entry, barricading themselves inside and trying to fight off the ensuing hoard. The Chronicler of the time, William of Newburgh states in his work “Historia Rerum Anglicarum” that “ Nevertheless, they kept off the besiegers with stones alone, which they pulled out of the wall in the interior. The castle was actively besieged for several days; and at length engines were got ready and brought up” The Rabbi realised that the likelihood of them getting out unscathed was not probable, and made the request for the man of the family to kill his spouse and children, and then take his own life. The estimate is around one hundred and fifty perished, but that was not the end of it as some of the survivors set fire to their belongings which caused the wooden structure to catch light. Terrified of being burned alive, they begged to be allowed to leave peacefully if they promised to convert to Christianity. Again, William of Newburgh talks about this in his historical accounts and mentions Richard Malbeste who – “a most daring fellow, were unmoved by pity for these miserable wretches. They deceitfully addressed kind words to them, and promised the favour they hoped, under the testimony of their faith, in order that they might not fear to come forth; but, as soon as they came out, those cruel swordsmen seized them as enemies, and slaughtered them in the midst of their continual cries for the baptism of Christ”. To finish it off completely, the mob made their way to the Catholic cathedral and burned every record of Jewish lending - which had been deposited there for safe keeping – to release all from their debts. You may wonder how Richard the Lionheart viewed this? he was incensed, and sent his chancellor, the Bishop of Ely to York to punish the perpetrators. Possibly knowing that they would be incurring the wrath of the King, many of the leaders had done a runner to Scotland, so in the end financial punishments were imposed on the families, the amount dependent upon their personal fortunes. Nobody was ever tried for the murder of this, but that mound that the current tower sits on must be holding awful secrets from this tragic event.

My goal with most of my short posts on the various social media sites is to get people thinking, get those who think it looks interesting to investigate and research further, but recently I fell afoul of the participants who want to be spoon fed everything – either that or confuse my thirty second highlights to be akin to full blown hundred thousand word doctoral thesis. I had read about the events in Tunguska on the morning of 30 th June 1908 and decided to put a short piece together about it. By short I mean, a burst, literally…about one hundred words and a thirty second video, I know I talk fast but even I cannot cover every single possibility in that so I had to cherry pick the most likely reasons – and include Aliens because why not? So, I look at the comments and see one word…Tesla. Ok cryptic, does the person mean the electric car or the amazing inventor who ironically I had mentioned in a podcast only recently. When I question this person further I get told that I should have mentioned Nikola Tesla with regards to Tunguska as if I had done my research thoroughly I would have known. Rude. For those of you who enjoy reading and watching posts put together by people like me thank you, and of course I am always more than happy to learn about a subject as I do not profess to be an expert in any way on everything but there are ways to do it. When putting information together quite frequently one has to decide what is going in and what is staying out, with a situation like Tunguska there were other possibilities and the potential death ray created by Tesla was one. I had chosen to exclude it because I thought an alien spaceship exploding was actually more probable than someone creating a ray which could reach from Long Island to a remote area of Russia without actually destroying anything else in its path. I think Tesla was amazing and light years ahead of his time with his theories, but we know he was working on wireless energy transmission in 1908, his Wardenclyffe tower. All the programmes I have watched, the articles I have read (a couple of which are linked below) look at this invention as something to transmit globally wireless communications (and subsequently energy). We also know that the brilliant inventor was working on weapons with his telautomaton (wireless torpedos), and that he believed “Tesla said his transmitter could produce 100 million volts of pressure and currents up to 1000 amperes, with experimental power levels of billion or tens of billions of watts. If that amount of power were released in "an incomparably small interval of time," the energy would be equal to the explosion of millions of tons of TNT, that is, a multi-megaton explosion. Such a transmitter would be capable of projecting the force of a nuclear warhead by radio. Any location in the world could be vaporized at the speed of light." (taken from Frank Germano at http://www.frank.germano.com/tunguska.htm ) - I do want to stress that I could not find the original source for this passage as the website is no longer active (PGM) When the actual website dedicated to Tesla thinks its in the realms of ridiculousness that his tower at Long Island could have been the cause of the explosion, then I believe them. Granted I am not a scientist and even have to google some of the terminology to put it into “doesn’t have a scooby” type language, the probability that a weapon that powerful could have been created in 1908 is somewhat hysterical. To stress my point, according to various sites it was not until 1934 that Tesla started talking about death rays, in actual fact he called it a death beam as he said “I want to state explicitly that this invention of mine does not contemplate the use of any so-called " death rays." Rays are not applicable because they cannot be produced in requisite quantities and diminish rapidly in intensity with distance. All the energy of New York City (approximately two million horsepower) transformed into rays and projected twenty miles, could not kill a human being, because, according to a well known law of physics, it would disperse to such an extent as to be ineffectual” ( https://www.pbs.org/tesla/res/res_art11.html ) When I posted on my private profiles how annoyed I was at the “do your research” type comment, a good friend (who shall remain nameless) who does a role very similar to mine said she frequently got “you didn’t mention xyz…” and gave up explaining that even in a thirty minute video you cannot always cover the entire history of something. So, firstly no I did not mention Tesla because I thought it was grasping at conspiratorial straws and I thought the three other possibilities were more viable (based on the scientific reports I had read), can I cover every single variation of theory in a thirty second video? Nope but do I appreciate a private message saying “have you read about….” Rather than a snarky “do your research” type post? hell yes. https://teslasciencecenter.org/history/tower/ https://www.teslasociety.com/tunguska.htm

“Fancy spending some time in a prison Penny? Promise we will let you leave in the end” well if that is the case it would be mighty rude of me to say no would it not? So, on a very cold night in December, just before Christmas, I am being driven by the lovely Chris to Ashwell prison in Rutland (second smallest “county” in England I will have you know…) , accompanied by my ever loyal son, Helen and Emily, we were off on an adventure. We were going to be joining my awesome Haunted Happenings friends on an investigation of the site, I had come well prepared with my staple Haribo and also so many layers of clothes I felt like one of those old 1970’s toys the Weeble’s, I could not put my arms down by my sides and was walking in a wide legged stance, when I sat on the floor bending forwards (which I can normally do with ease) was impossible, made me laugh anyway. Plot spoiler, even with all my thermals, fleece lined tights etc I was still absolutely freezing, but I guess we do not do this for comfort. There are three buildings that you can investigate on this site, E, F and G wing. Whilst the main prison built in 1955 was a lot larger, it was originally a category D facility which meant dormitory style blocks as opposed to individual cells. In 1987 it was re-categorised as a C, and the accommodation was changed slightly. One of the alterations implemented was the erection of a seventeen foot high security fence that year, the powers that be stated that it was absolutely nothing to do with the sixty or so prisoners who had escaped in the past year and everything to do with the category changing. It was also nothing to do with the fact that many of the higher security prisons were overcrowded and that Ashwell was under capacity…am I a cynic? Yes I think I may be. Anyway, whatever the true reasons were, problems did start to happen, a small group of prisoners caused £10,000 worth of damage to computers and office equipment in 2003, but in April 2009 there was a major riot. At around 2am on the morning of Saturday 11 th , the inmates started causing trouble, it is said that it was triggered by a 22yr old prisoner who refused to go back to his room. Much of the older block (the non- cellular part) was seriously damaged, and many of the four hundred or so occupants of that part had to be moved to other prisons whilst the Home secretary decided whether to fund the repairs or not. Before it was a prison, the site had been used by the US Army for a short while to train parachutists, ostensibly to replace those lost during the D Day landings, it was there from June 1944 to October of the same year. The Army having also been using nearby RAF Cottesmore from September 1943. What sort of experiences did we have whilst there? My son and I based ourselves in block E, the “cross” shaped building on the map. It still had some original cells as most have been altered to allow for the airsoft brigade who use the site on a regular basis, and we both felt that it had the best energy for us. Quite early on we were hearing noises in the cells, the wooden beds creaking as though someone was either turning or sitting on them, plus whilst stood outside in the corridor we saw the light coming through the window slightly obscured, had someone walked past it? It still did not feel ominous or that it wished us any harm whatsoever, in fact whatever was interacting with us had a cracking – if not slightly perverted – sense of humour as when I asked what they were doing for Christmas it replied with ; “myself” Now those of a nervous disposition who do not have a dirty sense of humour might be shocked, but I am neither and it made me absolutely cackle with laughter. That is not to say it was all fun and games, on a subsequent visit to the same floor where we had been having a good laugh with the spirits, something slightly darker had decided to pay a visit. Whilst my son is getting pretty experienced at what he does, I am still protective over him and when I could see that something was trying to unduly influence him (I posed the question, and he gave the most guttural grunt I have ever heard) angry Mumma bear stepped in and pulled him out of the situation. We went back down to the base room and he said that he could still feel the negativity and he did not like it one bit. I may have let rip slightly at this entity and told it to quite simply f**k off back to where it had come from. Now you may think that my dropping f bombs were just me being me, and yes it was to an extent, but it had also used that word to me when I was trying to communicate so I figured it was language it would understand. I then gave my son my obsidian necklace to wear, he told me the next day that as he was doing it up, he felt something tugging at it as though to remove it. Mother and son 1, nasty arsehole of a spirit 0 The experience finished with those remaining (around ten or so) doing some Estes work, that was quite productive and gave some interesting results – including me saying my name and then ready when Michael the team leader asked the spirit to say who had the headphones on. I love it when that happens. There are plenty of groups who visit Ashwell Prison, and whilst it has not the incarceration history of somewhere like Shepton Mallet, it definitely still has resident prisoners who want to interact. Check out www.hauntedhappenings.co.uk for more info.

I am always on the look out for an interesting story to share with you all, and once I decide on a theme, old newspapers are frequently a good place to start – and this is one of those such discoveries. As many of you know, I am a total sucker for early 20 th century aviation, but sadly a large number of the accounts do not have a happy ending to them but that does not mean we should not share them I feel. The Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail on the 28 th June 1957 reported that multiple people had seen a ghost on the Middleton St George RAF base and they firmly believed it was a pilot known as Squadron Leader McMullen. So, my research started… Middleton St George was predominantly a bomber base during the second World War, home to a variety of aircraft including Wellingtons, Lancasters and Halifax’s, pretty much the who’s who of WW2 heavy bombers, and knowing as we do the amount of fatalities that these crews were met with it is perhaps not surprising that such a large number seem to want to haunt their airfield. What of McMullen? Well, there is a clue as nearby is a street named McMullen Road, was this in homage to our supposed apparition? Yes is the answer. On the 13 th January 1945, Pilot Officer William McMullen of the Royal Canadian Airforce took off in his AVRO Lancaster KB793 from Middleton on a night cross country training exercise with a crew of seven in total. The take off was normal, as was the resulting three hour flight, but as the pilot started his descent from around ten thousand feet they noticed sparks coming out of the port outer engine (Lancasters had four engines in total). Despite turning the engine off, and feathering the prop to reduce drag, the pilot gave the order to bail out but he stayed in the aircraft to try and steer it away from the densely populated area of Darlington. His actions meant that by the time he was clear of the area and over Lingfield Farm, it was too late for him to escape and he died as the Lancaster crashed. He had started his flying on the 22 nd December 1941, achieving his “wings” on 6 th November 1942 and was in his early 30’s when he lost his life. Could it be Bill that is seen walking the runways and looking at the civilian aircraft that Middleton is now home to? I have no idea, but it is somewhat interesting that the unit he belonged to, the 428 was also known as the “ghost” squadron…

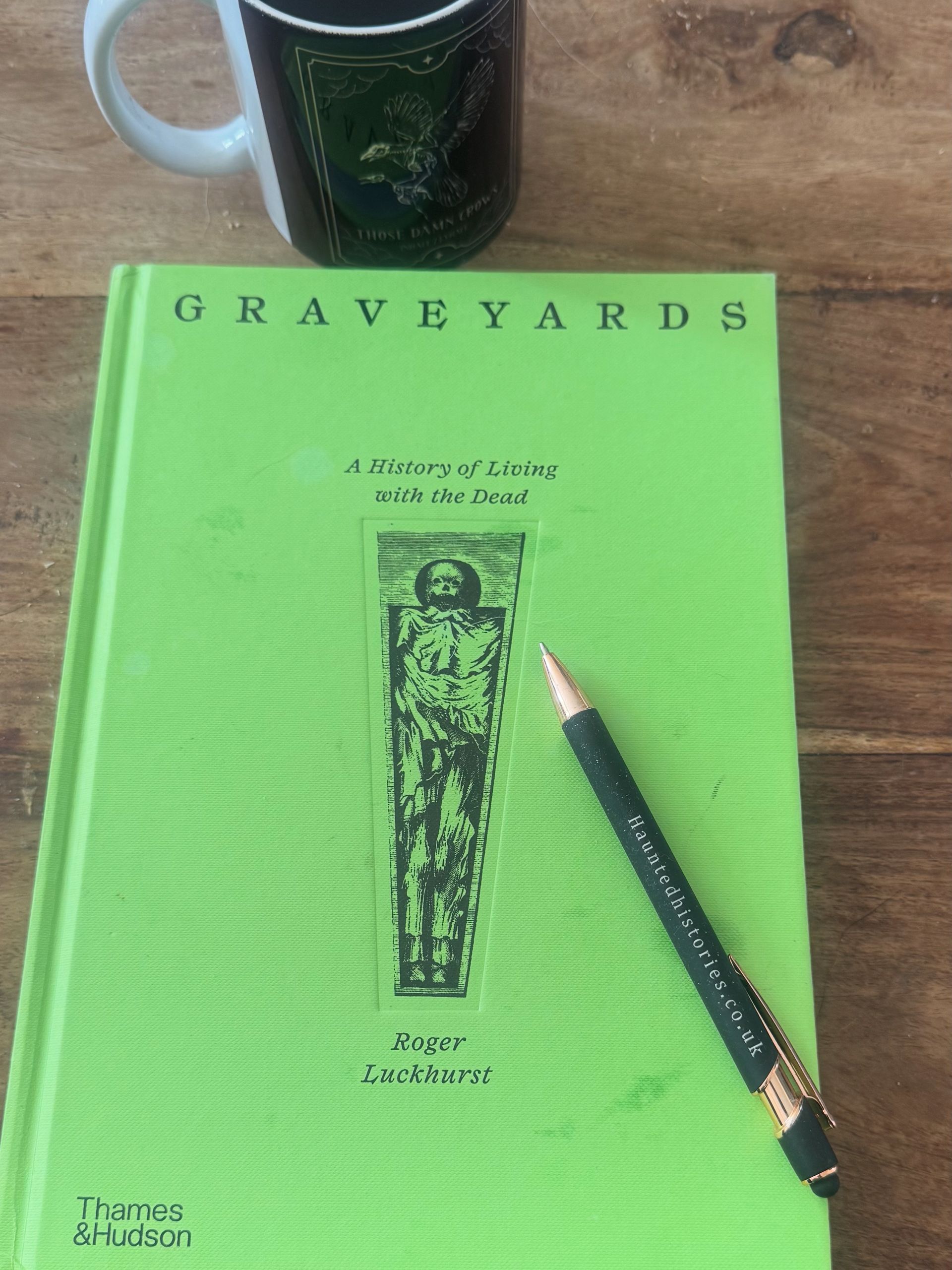

One of the coolest things that has happened since I have started to make a “name” for myself is that every so often I am asked to review a new tome that is coming out. For someone who is a self-confessed book worm, the opportunity to read pieces of work and comment on them is a dream quite literally come true. As a historian and a paranormal investigator, when the publisher Thames & Hudson asked me if I would like to read an advance copy of Professor Roger Luckhurst’s new book “Graveyards, a history of living with the dead” I positively jumped at the chance. I mentioned to my good friend Dr Kate Cherrell of Burials and Beyond that I was reading this and she was green with envy; she is the Queen of all thing’s death after all. Plot Spoiler, there was nothing I did not enjoy about this book so if you expect me to offer criticism, there is none, I have nothing but praise for this work. One of the early pieces of knowledge that Luckhurst gives us is that of Arnold van Gemep’s suggested three stage structure to all rites of passage, that being Separation, transition and incorporation. I am not going to explain what those mean, you can read the book and find out, but I do think that correlated nicely with the fact the work itself is split into three large sections, those being The Origins of Burial, Death and Faith and The Numberless Dead. What the author takes us on is not just a chronological but also an international journey through the different methods of dealing with the deceased, ranging from the obvious burial, cremation, mummification and even cannibalism. For those with an interest in the slightly folklore aspect and spooky, there is something there for you too. I was very pleased to see the legend of Timur (also known as Tamerlane) mentioned as this is one that has fascinated me for years. There is some very evocative writing as well that helps you visualise the incident such as when he is discussing what the bigger cities were going to do about their literally overflowing graveyards and this description of an event in Paris in relation to the Holy Innocents’ cemetery “…burst with the sodden weight of the dead. It released into the neighbouring streets a tsunami of bones and corpse wax - adipocere, the fat from human bodies. Nearby houses were inundated; some collapsed.” I mean pretty gruesome but it paints a very vivid picture of the problem that officials had, too many rotting bodies and not enough space. What I genuinely love about this book is that Luckhurst does not stay on one subject for too long and gives you just enough information to whet your appetite but leaves it up to you if you wish to do a deeper dive into that particular nugget or not. I find with some more academic driven pieces of work that they can labour on a specific point for far too long and you lose interest, not in this case. And for those who do not want to read too much, the pictures are pretty interesting too…

I have always been fascinated by killers, but not because I get a kick out of reading what they do, whilst I am not bothered by blood and gore, I am not interested in their methods of murder. What I truly find absolutely intriguing is the “why”, not just that, it is the lack of accountability in so many killers minds, the amount that blame either society or their victim for their crime. This case dates back to 1885, and it is not one that is well documented online, it is just a sad case of domestic violence with a fatal ending, but it is the lack of any kind of empathy for the woman he took the life of that has surprised me. There was something else that really bothered me about this whole case, none of the newspaper articles mentioned the name of the deceased, just called her “the wife”. 39 year old Owen McGill was living in a small tied cottage in Landican near Woodchurch (Cheshire) whilst he worked on a farm owned by Mr Ziegler, and carried out his tasks as both a waggoner and a farm labourer. On the 31 st October 1885, he had been on a trip to nearby Birkenhead and for some reason when he returned he got into an argument with some of the other labourers. His wife Mary came out to try and defuse the row and berated him in front of the others for starting such a pointless disagreement – or at least this is what witnesses reported to the police subsequently. That night his neighbours said they heard sounds of a woman shrieking and groaning in what they thought might be pain but they were too scared to get involved. What they had been privy to was Owen punching and kicking his wife Mary to death, in fact in the morning he cleaned up her body, and dressed her in clean white clothes. He then travelled into Birkenhead and called on a female married cousin of his, and asked her to return to Landican with him as he was concerned that his wife was unwell. One can but imagine what his relative thought they were going to encounter but the beaten corpse of his late wife was not one of them and his then employer was called who promptly arrested McGill for murder. Even at this point he had excuses, she had fallen out of his cart when she was inebriated so nothing to do with him, it had not been his fault as he was drunk and she knew he had a temper when alcohol was involved and that he had only struck her “once”, he finally admitted that it had rankled him that she thought her place was to tell him how to behave and found himself unable to stop the barrage of blows. Interestingly he had no family in England, but his parents and brother in county Louth Ireland refused to show him sympathy and alluded to the fact he had always used his fists with his wife and that he had treated her incredibly poorly. He spent the time from the murder until his execution on 22 nd February 1886 in Knutsford Gaol, and even there had not seemed to learned any lessons in humility and control being described as “low animal type and of ungovernable temper” having complained about the quality of the food in prison, demanding tobacco and finding his sentence amusing. Shortly before he was hanged, he did seem to suddenly realise that it was not one big joke and started to show that he accepted the penalty he had brought upon himself, but no, he still didn’t show any remorse or self-awareness and started to blame the neighbours for not intervening when he was beating his wife Mary to death. So, was there a “why” here? Probably not a logical one other than McGill had a problem with his temper and drink, and the combination of the two proved to be lethal for his wife Mary. Did he ever take true accountability for his crime? Reading his comments I genuinely do not think he ever did, he may have accepted what was going to happen shortly before he fell those five feet but he still blamed others for not having stopped him committing his crime in the mere moments before the handle was pulled.

Whilst trawling through newspaper articles from bygone times, looking for something that might interest me enough to spend a few hours – yes, it really does amuse me for that long – researching I stumbled across one headed up “stranger than fiction”, written by John Macklin and purported to be about a science master, Edward King, who in 1932 was working at University College School London – technically speaking it is actually in Hampstead but we will let that one slide. To caveat everything I am going to say, there is no where in this article does it state it is fiction, although then again it does not say it is fact either, but as it is entitled “Stranger than fiction” I would take it that we the reader are expected to believe it is true. The publication date is the 7 th October 1971, so is it an early Halloween spooky story? That I do not know, but I am going to tell you about it anyway. The author of this article talked about the fact that the school building was believed to be haunted back then, and the very stoic and scientifically minded King wanted to prove that all the weird noises that his colleagues (and pupils) heard in the corridors, the feelings of being shoved when in the cellars all had a very rational explanation and that he was determined to find them. One cold winters night in 1932 apparently – very ambiguous, always a huge red flag when it comes to accounts – Edward was in his study at the school marking papers, when suddenly he felt a severe temperature drop and an innate feeling of not being alone. Now those of us who have a penchant for ghost bothering can certainly identify with this, but it is not a flawless confirmation of a paranormal experience as we all know. Shortly after this he saw his papers start to move and get hurled across the room, at the same time a noise in the corridor outside which to King sounded like a flock of birds were flying at speed along the passageway. You will not be surprised to know that when he ventured out there – something as a person with a fear of birds, I would not have done – there was nothing…quite bemused he took himself to bed. The next morning, he went to his lecture room and found every single book thrown on the floor, was that the flapping noise he had heard? Being of the more pragmatic sort, King decided to find out who or “what” could have been causing this chaos, and decided it had to be Jeremy Bentham, the famous philosopher, jurist, social reformer and for many historians, the name inexorably linked with panoptical designed prisons. Why would this pioneer be haunting a school? King’s theory was that as Bentham had wanted his body to be donated to science that he was angry it had been mummified and then displayed at University College London – the further educational facility that was associated with the school. All this may very well be true, and Macklin was an author of true “ghostly” tales and published many books in the 1960’s and 1970’s on this very subject, however I have many buts with this account. Firstly, Bentham’s wishes were followed as best as they could, his body was dissected and then mummified with his head and skeleton on display – this was what his Last Will and Testament had requested. It is still viewable at UCL; however, the actual head is now locked away as the initial preservation was so poor that it started to look like a horrific caricature of the man rather than a homage to his achievements. Secondly, I can find no other accounts of hauntings and this type of poltergeist activity at the school documented online – if you know of any, please shoot it my way. And thirdly, I have found a few Edward Kings who were teachers in the London area in 1932, but they are all listed as elementary school teachers and not science masters, plus two of them were married in the 1921 census and to live on site, most teachers were single. One thing does interest me however, and may answer why nothing else at this level has been heard or seen, but could possibly be in about seven years’ time…Bentham died in 1832, this account is 1932 (although not the same time of year, Bentham passed in the June) so does that mean in 2032 the school may see some phenomenal activity when Jeremy himself - if it is Jeremy – comes back to make his presence felt?

I have never really fancied a flight on an airship, the thought of being supported by what is in effect a giant balloon has not got the same appeal as fixed or even rotary winged aircraft. Whilst I am fully aware that aircraft can go down regardless of how well built they are, the thought of being reliant upon an inflated piece of fabric is not one I want to explore. However back in the 1920’s society felt very different. The fact that this particular horrific crash is so well known, that not only has it featured in an episode of Dr Who, it has also had a song written about it by Iron Maiden. Let us go back first to where this airship was “born”, RAF Cardington near Bedford was originally built in 1915 to build and house two airships, R-31 and R-32, they were to be used by the Royal Navy as fleet protection but due to their completion being literally months before the end of the great war, they were never used. The site was then nationalised in 1919 and became known as Royal Airship works, five years later commencement of the R-101 project saw the hangar (which was already seven hundred foot long) being extended by over thirty feet in height and another one hundred foot in length. When you look at those measurements you can picture how huge this airship was going to be, once it was finished the R-101 (part of a pair of long distance dirigibles capable of flying within the British Empire) was huge, and the largest flying craft in operation at over seven hundred and thirty feet in length. After a year of testing, the length of the aircraft was increased by nearly fifty foot as it was decided more gas “bags” were needed to provide more lift…interesting Nevil Shute Norway - probably better known as author Nevil Shute – worked on the project and he said in his 1950’s biography that he felt the R-101 was” extravagant and over ambitious”. On the evening of the 4 th October 1930, R-101 took off from Cardington airfield on the start of her journey to Karachi, via Egypt (for a refuel). There were fifty four people on board, of those thirty seven were crew and then various officers and officials, the commander was Flight Lieutenant Carmichael Irwin, an incredibly experienced airship pilot who had joined the Royal Navy in 1915 and had returned to the programme in 1929 after working on balloons for a short period of time. When only twenty miles or so from Cardington they started to experience engine problems, having shut this one down they began to replace the oil gauge but did not report this back to control. Once they were over France, and there had been a change of those officers on duty, things started to go wrong. The airship dived, and whilst it recovered slightly, the pilot then in control reported that it was “flying heavy”, this meant she was relying on the lift from the forward thrust of the engines to keep her in the air as opposed to the gas which was meant to make her float…she went into a second dive around two and a half miles from Beauvais, from which she hit the ground and burst into flames, ultimately killing forty eight of her fifty four passengers. Most stories I have read about R-101 focus on the fact that the hangars at Cardington are reported to be haunted by some of the airmen who lost their lives that day, but I am going to mention what happened about three weeks after the disaster when psychic medium Eileen Garratt was conducting a reading at the National Laboratory of Psychical Research – whether you think that what she did was total hooey or actually there is validity in it, that is up to you. She is said to have made contact with Irwin, the commander of the airship, and the facts that she recorded were passed onto the inquest team but were deemed irrelevant as they could not accept information from a dead person. You can read the full transcript of what was said in John G Fuller’s book “The airmen who would not die” but to give you a little taster… “She was too heavy by several tons, and too amateurish in construction” “The gas skins are too porous and not strong enough” “One of the struts collapsed and caused a tear in the cover” All of these could have caused the problems they encountered, would Eileen Garratt really have been such an amazing “con woman” that she could have known that the tear in the nose cover would have caused the first dive, which would have damaged it further to give way to the second unrecoverable dive which took their lives? Makes you wonder.