The workhouse and you

Please sir, can I have some more...sources

Recently, a friend of mine, the Don’t scare Claire you tube channel released a video on the Thackray Museum of Medicine in Leeds (link here if you would like to watch it https://youtu.be/CrpD0j6JcYY?si=hc7sfrwYwa7tgD42) and it shocked many people that it had been the infirmary part of Leeds Poor Union Workhouse. The face of the show (funnily enough called Claire) had recently attended a talk I gave on a potted history of the Poor Union and it had made her want to learn more about the realities of the workhouse and whether it was the pits of hell or not.

Most people in the comments have been appreciative of the light that has been shone on the history, but some have accused anyone not condemning it as being right wing, or telling us that the writer Charles Dickens would have known more about it than we possibly could.

I thought that as the pen is mightier than the sword (Edward Bulwer Lytton 1839), I would put a short article together about this very subject.

Regarding Dickens, most people know that whilst I agree he could tell a ripping yarn, I am not a fan, and whether that makes me a bad historian is up for debate. The novel that tends to be cited when talking anything workhouse is Oliver Twist, and understandably so, but there are reasons I argue so vehemently against using that as a definitive type of historical evidence.

The Poor Law Amendment Act in 1834 was introduced with three primary goals in mind, reducing the cost of looking after the poor, taking beggars off the streets and encouraging those on the lower income end of the scale to work hard to avoid needing to ask for help. I guess those may seem like very conservative type actions, and could be said that the haves did not want to share with the have nots but up until this point, it was the responsibility of each Parish to care for their poor and that meant funds raised within said Parish as well. At this point, there are around fifteen thousand parishes in England and Wales, some with their own building that was allocated as a Parish workhouse, however during the collation of data to return to parliament “Abstracts of the returns made by the overseers of the poor” in 1776 (https://workhouses.org.uk/parishes/) it was reported that over £1.55million was being paid in poor relief, with only £80,000 of that going to the parish workhouse. This identified that ninety five percent was being given away in outdoor relief, which meant that it was very difficult to monitor the payments – not to mention how some parishes would have more needy than others, and the drain on the finances would be high.

To cut what could be a very long article short, parishes were put together to create Unions, each union was responsible to build a workhouse and the only way you could receive any type of poor relief would be by entering this establishment. That is not to say that outdoor relief ceased, it was at the discretion of the overseers who could offer it to those they thought deserving but the focus was to suggest they moved to the workhouse where the costs were spread out over all the “inmates”.

Back to Dickens, he wrote Oliver Twist around 1837, or it was at least serialised between 1837 and 1839, the Poor Law Amendment Act was 1834 with the first Poor union workhouse in Abingdon Berkshire being formed in 1835. The reason I highlight this is that the stereotypical “Victorian” workhouse was still very much in its infancy when the book was written, and much of the horror he describes can be traced back to the more unguided Parish Workhouse.

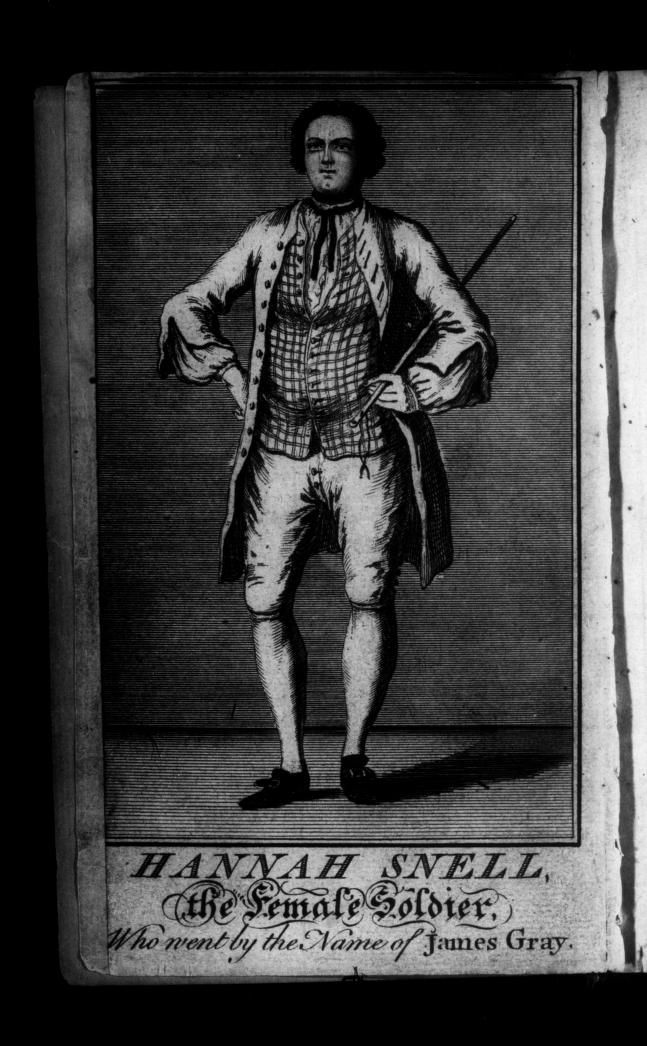

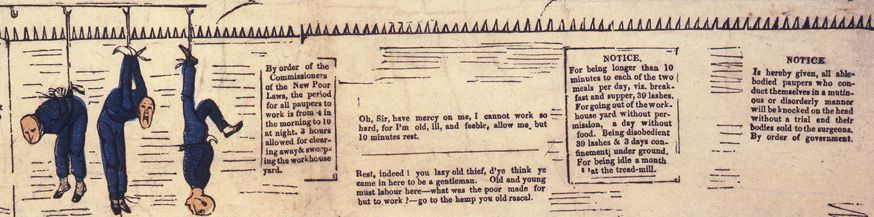

That aside, it is not surprising that Dickens picked up on something so topical as at the end of the day he wanted his work to sell, and there was a growing discontent with the new Poor Laws - as seen in the poster I have included in this article. Their day was heavily prescribed, with during the lighter months, the able bodied inmates would be expected to rise at 6am, have breakfast between 6.30 and 7am, then work until 12pm, to recommence at 1pm until 6pm – none of this 4am until 10pm with two ten minute breaks that the picture intimates.

By looking at the social climate of the time, whilst it is hard, especially so as a mother, to imagine my children over the age of seven being taken away from me, in the first half of the 19th century, progeny were not treated as being as precious as they are now. When you consider that it was not until the Mines and Collieries act 1842 that it banned boys under 10 years old to work underground that you realise that children in the poorer communities were a means to earn money to put bread on the table.

Is this right? from a conscientious point of view of course I do not think this is good or something I would want to see us go back to, but it was the time and the views of society then.

Let us go back to Oliver Twist, he asked for more…highly unlikely, food amounts were ordered to be weighed, and I do not know anyone who would want a pint and a half of gruel – although that was the adult allocation, children had less. The misappropriation of food is one of the reasons that the Andover scandal occurred, the master of the workhouse, Colin McDougal was not giving the inmates their allocation which was causing the starving masses in 1845 to fight over scraps of putrid meat and marrow that was still attached to the bones they were being told to crush.

Medical advancements did not understand nutrition at this point in time, therefore food was to fill you up and give you the energy to complete your tasks, and whilst the “menu” looks pretty dull and monotonous to us now, and meat being served three or four days a week. In an article published by the British Medical Journal, the author looks at the comparison of the workhouse diet in respect of Oliver wanting more and comes to the conclusion “The diet described by Dickens would not have supported health and growth in a 9 year old child, but the published workhouse diets would have generally met that need” (BMJ2008;337:a2722). Whilst there is not much written from people who experienced life in the workhouse, the common reason being they were illiterate, it is interesting that in “From workhouse to Westminster – the life story of Will Crooks MP” the author is not complimentary of the individuals experience of the workhouse, he does mention his mother crying as she was “…wondering where the next meal is coming from my boy” (page 3).

Was the workhouse a nice place to live? No, it was not meant to be, had it been akin to a hotel they would have been overrun with those wanting to live there – the undeserving and idle poor as they were known – but were all of them, and that is the important distinction, places of horror? Or were they an attempt at reducing the costs to the tax payer of maintaining individuals down on their luck with the resources they had available?

We do not have to agree on things, but if you are wanting to say to someone they are totally wrong, or insult them when they are trying to explain the situation and the logic behind the decision, rather than throw out terms such as “right wing”, or my personal favourite, “white supremacist Nazi”, give your point with sources and we can have an intelligent discussion.

…and please do tell me how we can go back in time and change it just to make you happy, that I would love to hear – what? you did not expect me to write something serious without a bit of sarcasm did you? This is not my degree thesis.