Poor Arthur...

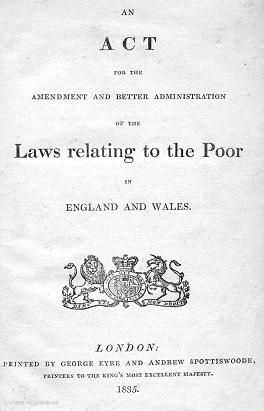

Everywhere you go, you can find traces of the Victorian era if you look close enough, especially the changes that they were looking to make to healthcare and the treatment of poverty. Due to the Lunacy Act of 1845, and also the County Asylums Act of the same year, counties had an obligation to provide care via a hospital setting for those with mental health problems – be they born with them or having developed them. One of the huge asylums that was built was known as the East Kent (or sometimes second Kent) County Asylum in Chartham, just south west of the more well known Canterbury.

Now those of you who are chomping at the bit to go and investigate, hold those horses as the site is now a housing estate with few parts of the original 19th century building remaining, but talking about Chartham is not the purpose of this piece, it is to tell you about one of its residents that met with a horrible end.

Arthur Izzard was born in Tonbridge in 1904, but by the age of 7 years old, he was in what was known as a “Farm Training Colony”, in Lingfield Surrey, and although the history books would describe these places as a type of industrial school for wayward children, in Arthur’s case it was to do with the fact he had epilepsy – as did every other boy on the census record of 1911, all of whom were under 16 years old.

Even though we do know that epilepsy is not a mental illness, it was many years before there was trustworthy treatment to help those having seizures, but my heart does truly break at the thought of so many children, taken away from their families and who were thrown together due to a neurological condition.

What is the link between Arthur and the hospital at Chartham? Some time between 1921 (when he was last mentioned on a census record) and 1938, he had been taken into East Kent and was there as a patient. According to reports he was one of the more “better off” of the residents, and would frequently lend money to others within the hospital but had a tendency to threaten reporting them to the Medical Superintendent if they did not pay him back in a timely manner. Obviously this did not make him a popular person, and according to the reports that the police were to subsequently obtain, he had made enemies within the hospital.

On the 22nd October 1938, Arthur had gone into Canterbury on his weekly shopping mission for the other patients as he was one of fifty nine who were allowed “out” of the hospital grounds. At some point along the way he was attacked, and suffered multiple blunt trauma wounds to his head, which proved fatal. He tried to stagger back to the asylum, but was found about twenty yards away from where he was assaulted, the money he was carrying for the others to pay for their purchases was stolen, as was his cap in which the thrifty Izzard had sewn his own cash.

It was quite obvious to the police who were investigating that it was someone who knew Arthur, who was aware of his weekly route and who also would have known that he had funds concealed inside his hat. They took copious statements, over two hundred according to reports, but this was not to be enough. The police had even put together a short list of suspects, with one having been seen near the vicinity of the murder, but the crime was never, ever solved, partly due to the realisation that a court would not take the evidence they had collated because it came from patients of an asylum.

With the capacity laws we have now, this kind of disregard for the ability of individuals with mental health problems being taken seriously would not happen, unfortunately those changes came too late for Arthur and his killer was never brought to justice.