The man behind the home

If you have listened to my recent podcast, with my guest the wonderful James Jefferies, where we discussed some of the superstitions and traditions shown by bomber crews during the Second World War, you would also have heard us mention a few names.

Guy Gibson – he of Dambuster’s fame – and also Leonard Cheshire, a name which anyone with a passing interest in bomber history is aware of, but in my experience many people are not and that is a great disservice to the man that he was.

James knows I am a massive Gibson groupie (there really is no other word for it!) and said that Cheshire seems to be overshadowed by the former in the history books and people’s memory, I actually agreed, he is and unfairly so. My belief is that because Guy died as a very young man and under slightly unknown circumstances, was it pilot error? Was it due to friendly “fire” or was he taken out by a Luftwaffe pilot during a mission? Personally, my view is that it was a combination of perceived invincibility, arrogance and exhaustion that led to ultimately a fatal pilot mistake. Many of the posthumous comments made about Gibson did state that he was incredibly pompous and had absolute self-belief in his own abilities, as this blog is not about Guy, I am not going to share my thoughts on that but Cheshire was the polar opposite in personality, and perhaps that is why he survived three tours on bombers during the war.

Read any of the books he has written, and do not forget to get hold of a copy of Tail Gunner by Richard C Rivaz, the title tells you what his role was, but perhaps it is better to read what one of the flight crew felt about their pilot than how he came across in print. Cheshire had an incredibly hard working and studious approach to being a pilot, he took the responsibility with uber seriousness and whilst he was training under Hugh “lofty” Long, he would be expected to repeat tests and scenarios until he was absolutely perfect. This gave him a sense of caution which is perhaps why, after he was made a Group Captain at RAF Linton on Ouse, for 76 Squadron, he still flew on missions, albeit a few times a month (apparently the Commanding Officer was only meant to fly once a month, unless it was absolutely necessary, Cheshire always found a reason to meet that criteria). He had an amazing knack for making novice crews feel at ease, and was always looking at ways to improve the men’s morale and lot. Flying Handley Page Halifax’s out of Yorkshire, they were not able to reach such high altitudes as the Lancasters, so were more susceptible to flak than their higher flying sister. Cheshire looked at reducing the weight of the aircraft under his command and subsequent losses were reduced = improved morale.

I am fast forwarding through four years of constant work here, but I would need thousands upon thousands of words to correctly put into print the amazing achievements of this man. It is believed it was his experience of seeing the second nuclear bomb dropped on Nagasaki on 9th August 1945 that changed his outlook somewhat.

“We are faced either with the end of this country, or the end of war. Ending war and making a better future is not a responsibility that we can say belongs exclusively to the government …each one of us must play our part.”

This is the same person who was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross, two bars to his Distinguished Service Order and a Victoria Cross, so why have so many people not heard of him?

If I were to say “Cheshire Homes”, you may know of one? I certainly grew up near to the place in East Carleton Norfolk, and as a Brownie and Girl Guide (yes, I was young once!) we would regularly help at the summer fete with our stall selling groceries but we never saw the people who lived there and I wondered why.

When I became older, I learned that Cheshire Homes were actually founded by…Leonard – actually, he was also married to another amazing charity founder, Sue Ryder, that is one humanitarian powerhouse of a couple! It is the story of how it happened however that is well worth reading about.

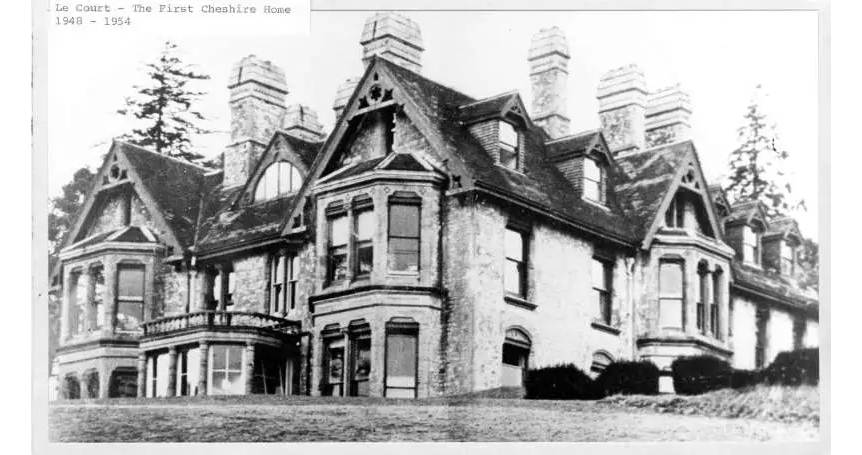

After the war had ended, Cheshire was still looking for meaning in his life and started a communal living project entitled “Vade in Pacem” to help former service personnel transition back to civilian life, unfortunately that did not work out but he heard that a former member of the experiment, one Arthur Dykes, needed somewhere to live and had asked Cheshire if he could park his caravan on the site of Le Court, Hampshire. This gave Leonard his purpose back, and he proceeded to learn nursing skills to help both former army veteran Arthur – who unbeknown to the patient, had a terminal cancer diagnosis – and by 1949, twenty four other residents.

Whilst initially he may have veered more towards ex service personnel, now the many homes set up in his name are a place of safety for people with severe disabilities, whether physical or learning, and all due to one person having seen the worst of humanity, wanting to give something back. It is slightly tragic however, that Cheshire passed away after being diagnosed with Motor Neurone Disease at the age of 74, the youngest ever Group Captain in the R.A.F certainly left an amazing legacy.